|

| |

48th Berlin

International

Film Festival (1998)

feature by Eddie

Cockrell

Notes from the Festival

These are capsule reviews of selected films caught

during the 48th Berlin International Film Festival, 11 – 22 February 1998. Each film

– referred to by it's English title as opposed to the original language – is

followed by the name of the section in which it appeared in parentheses. Longer reviews of

some films will follow, based on US festival dates and/or domestic acquisition and

distribution schedules.

With literally hundreds of films available throughout the day (and well into the

night), how does one decide what to see? Research, for one thing: the Berlin festival is

unsurpassed in available documentation – presskits circulate on the higher-profile

films (easily obtainable via the well-staffed pressbox area), and the daily festival

magazine offers capsule reviews, background information and interviews. Networking helps,

among friends and colleagues who may have seen certain films at previous festivals or, as

the festival progresses, earlier showings of films. Finally (and perhaps most obvious),

one's particular agenda dictates the schedule: in this case, the goal was to see certain

international films that might appear at two east coast festivals that had offered note

writing assignments (this explains why so many of the following films were screened in the

market section, which is traditionally skewed towards films that have already played other

festivals and are in search of buyers based on reputation).

So, to the films:

An absorbing three-hour

epic marred only by the emotionally high-pitched dramatic interludes, Sergio Rezende's The

Battle of Canudos (Panorama) came to Berlin as last year's domestic box office

champion in Brazil – and, at $6 million, the most expensive in the history of the

resurgent industry there. The film is based on a bloody episode in the country's history a

little over a hundred years ago, as government soldiers clashed with the 25,000 residents

of the eponymous village over their fealty to religious leader Antonio Conselheiro (played

by José Wilker, star of Carlos Diegues' 1979 success Bye Bye Brazil). Filmed with

undeniable force and laced with extraordinary battle scenes, the film loses direction and

energy during the melodramatic lulls in the action, as a daughter of the village defies

her devout father and marries a soldier who becomes one of the attacking forces. "The

film talks about religious fanaticism and the conflict between two worlds," explained

Rezende in Berlin. "Sadly, in many countries this theme continues to be as relevant

today as in the past." Perhaps the movie plays better as a four-part television

presentation, which the press flier indicates is available for international sales. An absorbing three-hour

epic marred only by the emotionally high-pitched dramatic interludes, Sergio Rezende's The

Battle of Canudos (Panorama) came to Berlin as last year's domestic box office

champion in Brazil – and, at $6 million, the most expensive in the history of the

resurgent industry there. The film is based on a bloody episode in the country's history a

little over a hundred years ago, as government soldiers clashed with the 25,000 residents

of the eponymous village over their fealty to religious leader Antonio Conselheiro (played

by José Wilker, star of Carlos Diegues' 1979 success Bye Bye Brazil). Filmed with

undeniable force and laced with extraordinary battle scenes, the film loses direction and

energy during the melodramatic lulls in the action, as a daughter of the village defies

her devout father and marries a soldier who becomes one of the attacking forces. "The

film talks about religious fanaticism and the conflict between two worlds," explained

Rezende in Berlin. "Sadly, in many countries this theme continues to be as relevant

today as in the past." Perhaps the movie plays better as a four-part television

presentation, which the press flier indicates is available for international sales.

Beware of guilty pleasures, as they're liable to lead to

disappointment. This was the lesson of The Big Lebowski

(Competition), which had it's world premiere screening complete with co-star John Goodman

and co-creators Joel and Ethan Coen in attendance.  After the humanistic lull of Fargo

(which was built around Oscar-winning Frances McDormand – Joel's wife), the brothers

are back in full sardonic mode in this surrealistic black comedy of mistaken identity,

kidnapping and who knows what else (they're sure not telling). Jeff Bridges is fitfully

funny as Jeff "The Dude" Lebowski, a laid-back stoner in early 1990's Los

Angeles who becomes the target of all sorts of lowlife elements when he is mistaken for

another Lebowski, an unrelated Pasadena millionaire whose wife has been kidnapped. Can The

Dude stay awake long enough to find the missing Bunny (for that is the millionaire's

wife's name)? Can the audience stay awake long enough to see this absurdist reduction of The

Big Sleep to it's inevitably illogical conclusion? As in Barton Fink, the Coens

here exhibit a contemptuousness towards their characters as well as an almost open

hostility towards anyone unfortunate to wander into the theater (ironically, Barton

Fink won the grand prize at Cannes – where The Big Lebowski was expected

to premiere). Goodman is boisterous as Dude's buddy Walter, but Steve Buscemi, Julianne

Moore, Peter Stormare and John Turturro barely register in support as cryptic, one-joke

characters. And the lesson? Never spend time watching a movie that can be seen after a

festival. After the humanistic lull of Fargo

(which was built around Oscar-winning Frances McDormand – Joel's wife), the brothers

are back in full sardonic mode in this surrealistic black comedy of mistaken identity,

kidnapping and who knows what else (they're sure not telling). Jeff Bridges is fitfully

funny as Jeff "The Dude" Lebowski, a laid-back stoner in early 1990's Los

Angeles who becomes the target of all sorts of lowlife elements when he is mistaken for

another Lebowski, an unrelated Pasadena millionaire whose wife has been kidnapped. Can The

Dude stay awake long enough to find the missing Bunny (for that is the millionaire's

wife's name)? Can the audience stay awake long enough to see this absurdist reduction of The

Big Sleep to it's inevitably illogical conclusion? As in Barton Fink, the Coens

here exhibit a contemptuousness towards their characters as well as an almost open

hostility towards anyone unfortunate to wander into the theater (ironically, Barton

Fink won the grand prize at Cannes – where The Big Lebowski was expected

to premiere). Goodman is boisterous as Dude's buddy Walter, but Steve Buscemi, Julianne

Moore, Peter Stormare and John Turturro barely register in support as cryptic, one-joke

characters. And the lesson? Never spend time watching a movie that can be seen after a

festival.

Much the same kind of criticism can be applied to The Big One

(Forum), the latest screed from shambling do-gooder Michael Moore. Filmed during the

three-month 1996 book tour for "Downsize This!," the film finds the petulant

mischief-maker attempting to meet at least one CEO of a successful company in the 50

cities he blows through, with side trips to the Payday candy factory in Centralis,

Illinois and visits with Cheap Trick's Rick Nielsen and a prison inmate who answers

customer inquiries on the TWA toll-free telephone line. As in Roger & Me, much

of this material is fluid and funny (particularly the climactic meeting with an obviously

uncomfortable Phil Knight at Nike), and there's no denying the legitimacy of the cause:

championing the rights of the average working stiff. But Moore's credibility is severely

undercut by his overly subjective and often offensive manner (a sequence where he

persuades a clueless security guard to throw one of his regional handlers out of a mall is

an appalling low point). Moore's heart is in the right place, but he hasn't yet figured

out that this Crusader Rabbit routine can be run by just about anyone with an attitude and

a camera crew; the failure of both his television show and dramatic feature debut (Canadian

Bacon) suggests that like a poor musician, Moore only has one note but figures if he

plays it loud enough, people will listen. Much the same kind of criticism can be applied to The Big One

(Forum), the latest screed from shambling do-gooder Michael Moore. Filmed during the

three-month 1996 book tour for "Downsize This!," the film finds the petulant

mischief-maker attempting to meet at least one CEO of a successful company in the 50

cities he blows through, with side trips to the Payday candy factory in Centralis,

Illinois and visits with Cheap Trick's Rick Nielsen and a prison inmate who answers

customer inquiries on the TWA toll-free telephone line. As in Roger & Me, much

of this material is fluid and funny (particularly the climactic meeting with an obviously

uncomfortable Phil Knight at Nike), and there's no denying the legitimacy of the cause:

championing the rights of the average working stiff. But Moore's credibility is severely

undercut by his overly subjective and often offensive manner (a sequence where he

persuades a clueless security guard to throw one of his regional handlers out of a mall is

an appalling low point). Moore's heart is in the right place, but he hasn't yet figured

out that this Crusader Rabbit routine can be run by just about anyone with an attitude and

a camera crew; the failure of both his television show and dramatic feature debut (Canadian

Bacon) suggests that like a poor musician, Moore only has one note but figures if he

plays it loud enough, people will listen.

Okay, so the opening night film The Boxer (Competition) was

already playing commercially well before the festival, but one can't see everything –

and besides, one always likes the see the opening night film to gauge the mood of the

audience (not to mention the jury, the 1994 edition of which gave the Golden Bear grand

prize to the previous collaboration between director Jim Sheridan and actor Daniel

Day-Lewis, In the Name of the Father). Although it didn't win any official festival

awards (a 25-member jury from the daily "Berliner Morgenpost" named it "the

best public entertainment film of quality"), The Boxer was well-received

indeed, as befits it's serious intentions. Daniel Day-Lewis is Danny Flynn, an IRA

activist who returns home after 14 years in prison. Deciding to reopen a closed gymnasium

that featured a popular youth boxing program, Danny also is drawn into a reignited

relationship with Maggie (Emily Watson), with whom he'd been involved before imprisonment

but is now married to his best friend. Although the relatively tepid showing of the film

in North America has been credited to the weighty social issues and the American ignorance

of them, The Boxer is an earnest, involving and ultimately rewarding film that

should do well on video (as more thoughtful films tend to do). Okay, so the opening night film The Boxer (Competition) was

already playing commercially well before the festival, but one can't see everything –

and besides, one always likes the see the opening night film to gauge the mood of the

audience (not to mention the jury, the 1994 edition of which gave the Golden Bear grand

prize to the previous collaboration between director Jim Sheridan and actor Daniel

Day-Lewis, In the Name of the Father). Although it didn't win any official festival

awards (a 25-member jury from the daily "Berliner Morgenpost" named it "the

best public entertainment film of quality"), The Boxer was well-received

indeed, as befits it's serious intentions. Daniel Day-Lewis is Danny Flynn, an IRA

activist who returns home after 14 years in prison. Deciding to reopen a closed gymnasium

that featured a popular youth boxing program, Danny also is drawn into a reignited

relationship with Maggie (Emily Watson), with whom he'd been involved before imprisonment

but is now married to his best friend. Although the relatively tepid showing of the film

in North America has been credited to the weighty social issues and the American ignorance

of them, The Boxer is an earnest, involving and ultimately rewarding film that

should do well on video (as more thoughtful films tend to do).

A highlight of the festival that went curiously unrewarded by the

jury, the Australian drama The Boys (Competition) features an extraordinary

performance by David Wenham (who also co-produced) as Brett Sprague, one of three brothers

in a poor dysfunctional family in contemporary Sydney. Covering essentially the 24 hours

between Brett's release from prison and reincarceration, the film uses an exhilaratingly

complex flashback and flash forward structure to illustrate events that happened on either

side of the fateful day. The movie is based on a 1991 play that in turn takes as it's

hideous inspiration the brutal assault and murder of a nurse in the Australian city some

years before. Toni Collette, so beguiling in Muriel's Wedding, is pure raw emotion

as Brett's long-suffering girlfriend, while Lynette Curran, with Wenham the only holdover

from the stage production, is affecting as the ineffective mother of this deadly trio.

Shot in claustrophobic close-ups and without any explicit violence, The Boys is

emotionally devastating nonetheless, using a real-life tragedy as the springboard for a

story of mounting frustration and rage that could well be set in just about any country in

the world. A highlight of the festival that went curiously unrewarded by the

jury, the Australian drama The Boys (Competition) features an extraordinary

performance by David Wenham (who also co-produced) as Brett Sprague, one of three brothers

in a poor dysfunctional family in contemporary Sydney. Covering essentially the 24 hours

between Brett's release from prison and reincarceration, the film uses an exhilaratingly

complex flashback and flash forward structure to illustrate events that happened on either

side of the fateful day. The movie is based on a 1991 play that in turn takes as it's

hideous inspiration the brutal assault and murder of a nurse in the Australian city some

years before. Toni Collette, so beguiling in Muriel's Wedding, is pure raw emotion

as Brett's long-suffering girlfriend, while Lynette Curran, with Wenham the only holdover

from the stage production, is affecting as the ineffective mother of this deadly trio.

Shot in claustrophobic close-ups and without any explicit violence, The Boys is

emotionally devastating nonetheless, using a real-life tragedy as the springboard for a

story of mounting frustration and rage that could well be set in just about any country in

the world.

A strong return to the eccentric soul of it's 1960s heyday, the

Czech television production Buttoners (European Film Market) is a quirky, hugely

enjoyable treatise on fate, coincidence and redemption that uses a late-night radio talk

show to stitch together six seemingly unrelated but actually interlocking stories. From

the opening sequence, which juxtaposes a heated discussion of the weather and profanity in

Kokura, Japan as the Enola Gay prepares to bomb the city but is diverted at the last

second to Hiroshima, through to the final episode, which finds the American pilot of the

craft summoned via seance to speak on the radio program of forgiveness and tolerance, Buttoners

has all the energy, black comedy and self-indulgent irony of the best Czech movies (Jiri

Menzel is even mentioned explicitly in one sequence). Winner of a Tiger Award at the

recent 33rd International Film Festival Rotterdam, Buttoners is sure to do the

North American film festival circuit later this year and in early 1999, most probably

commencing with a premiere screening at the Toronto festival this fall.

Unfortunately, the new

Slovak cinema isn't yet as prolific or successful as that of it's former confederate, and

although it tries mightily for the same kind of ironic absurdity as Buttoners, The

Camp of Fallen Women (Panorama) is ultimately undone by a slack pace, cliched

characters and an unfocused script. The time is the late 1940s, and prostitutes are being

rounded up on the streets of Bratislava (the Slovak capital) for transport to a forced

labor camp for "re-education." Once there they become swept up in the power

struggle endemic to all such prisons and camps: the unnamed Commandant (Stefan Kvietik) is

an ok sort, but his aide Lieutenant Plazak (Jozef Vajda) is a sadistic hard-liner whose

efforts are tempered only slightly by cynical Dr. Zigmund, a Jew who apparently dates from

the days when the camp was used to detain them instead of general undesirables. The movie

has a genuinely intriguing premise, but it is short-circuited at every turn by Anton

Balaz' pokey script (adapted from his novel, which may be a large part of the problem) and

the diffident direction of Laco Halama. And, fatally, the handful of women on whom the

film dwells never emerge as distinctive or empathetic characters, leaving the whole

enterprise lifeless and occasionally distasteful. Neither fish nor fowl, The Camp of

Fallen Women is nowhere near as trashy as the title might lead the consumer to

believe, nor as socially significant as a movie on this provocative subject could have

been. Unfortunately, the new

Slovak cinema isn't yet as prolific or successful as that of it's former confederate, and

although it tries mightily for the same kind of ironic absurdity as Buttoners, The

Camp of Fallen Women (Panorama) is ultimately undone by a slack pace, cliched

characters and an unfocused script. The time is the late 1940s, and prostitutes are being

rounded up on the streets of Bratislava (the Slovak capital) for transport to a forced

labor camp for "re-education." Once there they become swept up in the power

struggle endemic to all such prisons and camps: the unnamed Commandant (Stefan Kvietik) is

an ok sort, but his aide Lieutenant Plazak (Jozef Vajda) is a sadistic hard-liner whose

efforts are tempered only slightly by cynical Dr. Zigmund, a Jew who apparently dates from

the days when the camp was used to detain them instead of general undesirables. The movie

has a genuinely intriguing premise, but it is short-circuited at every turn by Anton

Balaz' pokey script (adapted from his novel, which may be a large part of the problem) and

the diffident direction of Laco Halama. And, fatally, the handful of women on whom the

film dwells never emerge as distinctive or empathetic characters, leaving the whole

enterprise lifeless and occasionally distasteful. Neither fish nor fowl, The Camp of

Fallen Women is nowhere near as trashy as the title might lead the consumer to

believe, nor as socially significant as a movie on this provocative subject could have

been.

One of two films on the great director to be

featured in Berlin this year, Eisenstein: The Master's House (Forum) uses

documentary footage of the filmmaker at work and in repose as well as unconnected

historical images to evoke the life and times of perhaps the greatest theoretician the

movies has ever known. Together with the second work, Oleg Kovalov's Sergei Eisenstein:

Mexican Fantasy (about the making of the uncompleted Que Viva Mexico! and also

shown in the Forum), they provide exhaustive information on Eisenstein's methods, impact

and experiences.

A more contemporary film from the same part of the

world, Vyachelsav Krishtofovich's Ukranian-French co-production A Friend of the

Deceased (European Film Market) illustrates that in the east, the winds of social

change haven't been as benevolent and enriching for all in equal measure. It is that

economic and moral confusion which is at the heart of this fine new film from the director

of Adam's Rib. Long-suffering Anatoli (Alexander Lazarev) is a struggling

Kiev-based translator whose estranged wife still sleeps in their bed and coos into a cell

phone while he makes do on the couch and awkwardly conducts what little business comes his

way on the speakerphone of an otherwise busted handset. When she finally leaves him, his

utter despair manifests itself in odd jobs and a bizarre plot or two. His only salvation

would appear to be two very different women. With Lazarev's perfectly calibrated hangdog

performance balancing the dry, precise tone, Krishtofovich's intentions are clear:

"In Ukrainian," he says, "the word 'love' and the word 'pity' are sometimes

considered synonyms. That is why I made this film about people whom I pity. And whom I

love."

One strong hint that Manhattan-based indie veteran Amos

Poe's mischievous, bloody, hilarious and altogether invigorating new movie Frogs For

Snakes (Forum) is up to more than initially meets the eye is the basic structure,

which offers the conventional opening credits nearly 20 minutes into the picture and quite

literally doesn't want to stop (audiences are advised to keep their seats until the lights

come up to make sure they've really seen the whole thing). A spectacular mixture of Poe's

fiercely independent spirit with recognizably conventional moviemaking elements, Frogs

For Snakes transports such recognizable stars as Barbara Hershey and Harry Hamlin to a

hip, intimate milieu. She's Eva, one of a tangled web of downtown denizens involved in

murder and double-cross – when she's not walking her kids to school, working at a

local greasy spoon or practicing the numerous monologues from classic movies and plays

that punctuate the action. And she's not alone: everybody's doing it, furiously brushing

up for, among other things, the upcoming production of David Mamet's "American

Buffalo" being mounted by local kingpin Al Santana (Robbie Coltrane) – who also

happens to be Eva's ex. It's a grand idea played with knockabout abandon, but then... as

the monologues mount up as quickly as the bodies (a gory bar shootout is a what-the-hell-was-that

highlight), Frogs for Snakes becomes something much deeper, a heartfelt examination

of the creative process that percolates along at with it's own defiant and beguiling pace.

Much of the movie's fun, in fact, comes from watching the actors perform the often lengthy

speeches in character with varying degrees of success – as well as trying to

guess which film or play the monologues come from (standouts include Lisa Marie's

on-purpose groaner from The Hustler and Hamlin's dead-on deathbed recitation from

the Mamet play). Poe's been making this kind of movie both in and out of the mainstream

for over two decades (Subway Riders, Joey Breaker, the script for Rocket

Gibraltar) and it must be a source of bittersweet vindication to see his one-of-a-kind

sensibility co-opted by a newly hipper-than-thou Hollywood. But make no mistake about it: Frogs

For Snakes (the title is explained – but not here) represents the real deal, a

wild and woolly paeon to the durability of family, the passion of expression and the joys

of life in Lower Manhattan.

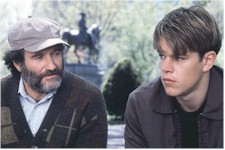

With all it's acclaim and Oscar

nominations, one of the chief strengths of Gus Van Sant's Good Will Hunting

(Competition) often gets lost in the hubbub. That would be the storytelling skills and

visual high-rolling of Van Sant himself, who brings to the pleasant underdog tale (by lead

actors Matt Damon and Ben Affleck) the same dreamy – some say druggy – style

that put him on the map with Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho.

Should Damon in particular go from his Silver Berlin Bear for single achievement as

co-scripter and actor to Academy Awards in the same categories, it is hoped that he will

remember to dance with who brung him and thank Van Sant for his subtle but inestimable

contribution to the film's success. With all it's acclaim and Oscar

nominations, one of the chief strengths of Gus Van Sant's Good Will Hunting

(Competition) often gets lost in the hubbub. That would be the storytelling skills and

visual high-rolling of Van Sant himself, who brings to the pleasant underdog tale (by lead

actors Matt Damon and Ben Affleck) the same dreamy – some say druggy – style

that put him on the map with Drugstore Cowboy and My Own Private Idaho.

Should Damon in particular go from his Silver Berlin Bear for single achievement as

co-scripter and actor to Academy Awards in the same categories, it is hoped that he will

remember to dance with who brung him and thank Van Sant for his subtle but inestimable

contribution to the film's success.

Takeshi Kitano employs a more rigorous style for Fireworks

(European Film Market); the Japanese title Hanabi means just that; a hyphen in the right

place splits it into flower ("hana") and fire ("bi") – or, in the

steely morality of this exquisitely cool drama (punctuated by the director's paintings),

life and death. Dedicated Detective Nishi (Takeshi, acting under his popular nickname

"Beat") watches his world collapse, as wife Miyuki (Kayoko Kishimoto) is

diagnosed with a terminal illness just as his partner Horibe (Ren Osugi) is ambushed by

some underworld punks. Faced with a dying spouse and a crippled partner, the moral,

compassionate Nishi impassively puts his house in order the only way he knows how:

decisive, violent action. By turns tender and brutal, Fireworks provides plenty of

them, set against a beautiful but disconcerting mix of urban and rural Japan and scored to

Joe Hisaishi's lush, reflective score. The prolific Takeshi calls film a "luxurious

toy"; Fireworks – already winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice festival and

gathering substantial critical momentum stateside – is one hell of a playtime. Takeshi Kitano employs a more rigorous style for Fireworks

(European Film Market); the Japanese title Hanabi means just that; a hyphen in the right

place splits it into flower ("hana") and fire ("bi") – or, in the

steely morality of this exquisitely cool drama (punctuated by the director's paintings),

life and death. Dedicated Detective Nishi (Takeshi, acting under his popular nickname

"Beat") watches his world collapse, as wife Miyuki (Kayoko Kishimoto) is

diagnosed with a terminal illness just as his partner Horibe (Ren Osugi) is ambushed by

some underworld punks. Faced with a dying spouse and a crippled partner, the moral,

compassionate Nishi impassively puts his house in order the only way he knows how:

decisive, violent action. By turns tender and brutal, Fireworks provides plenty of

them, set against a beautiful but disconcerting mix of urban and rural Japan and scored to

Joe Hisaishi's lush, reflective score. The prolific Takeshi calls film a "luxurious

toy"; Fireworks – already winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice festival and

gathering substantial critical momentum stateside – is one hell of a playtime.

In the Canadian-funded documentary Hollywoodism:

Jews, Movies and the American Dream (Panorama), director Simcha Jacobovici uses Neal

Gabler's book "An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood" to put

forward the theory that the American dream in studio classics of yesteryear was less a

reflection of the country's history than the idealized fantasies of the first immigrant

moguls, men like Carl Laemmle (Germany), Harry Warner and Sam Goldwyn (Poland), William

Fox and Adolph Zukor (Hungary), and Russia's own Louis B. Mayer. Archival footage and

rare, revealing home movies mix with identifiable film clips to bolster the argument,

which is credible as far as it goes but is often rather more convenient than the

complicated history of the movie business would suggest. Still, this is a natural for

general and specialty festivals and should spark constructive debate wherever it is shown. In the Canadian-funded documentary Hollywoodism:

Jews, Movies and the American Dream (Panorama), director Simcha Jacobovici uses Neal

Gabler's book "An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood" to put

forward the theory that the American dream in studio classics of yesteryear was less a

reflection of the country's history than the idealized fantasies of the first immigrant

moguls, men like Carl Laemmle (Germany), Harry Warner and Sam Goldwyn (Poland), William

Fox and Adolph Zukor (Hungary), and Russia's own Louis B. Mayer. Archival footage and

rare, revealing home movies mix with identifiable film clips to bolster the argument,

which is credible as far as it goes but is often rather more convenient than the

complicated history of the movie business would suggest. Still, this is a natural for

general and specialty festivals and should spark constructive debate wherever it is shown.

Jackie Brown

(Competition) has been reviewed by Nitrate Online, but is worth revisiting briefly

to report that for the most part the international critics "got" the film in a

way their American colleagues didn't. True, the references to vintage cop TV shows of the

1970s don't travel well, but they're not expected to (and these references went over the

head of the majority of critics anyway); what the Berlin audiences responded to was

exactly what director Quentin Tarantino has been criticized for: the controversial

portrayal of black culture and speech – much of which is lifted directly from Elmore

Leonard's novel. The International Jury apparently agreed, awarding Samuel L. Jackson the

Silver Berlin Bear for Best Actor. This is why some directors push for their films to be

accepted in Berlin competition; it's sort of a court of second appeal for movies that

might have been misunderstood and/or misappreciated at home. Jackie Brown

(Competition) has been reviewed by Nitrate Online, but is worth revisiting briefly

to report that for the most part the international critics "got" the film in a

way their American colleagues didn't. True, the references to vintage cop TV shows of the

1970s don't travel well, but they're not expected to (and these references went over the

head of the majority of critics anyway); what the Berlin audiences responded to was

exactly what director Quentin Tarantino has been criticized for: the controversial

portrayal of black culture and speech – much of which is lifted directly from Elmore

Leonard's novel. The International Jury apparently agreed, awarding Samuel L. Jackson the

Silver Berlin Bear for Best Actor. This is why some directors push for their films to be

accepted in Berlin competition; it's sort of a court of second appeal for movies that

might have been misunderstood and/or misappreciated at home.

In Pal Sletaune's deceptively ramshackle Junk Mail

(European Film Market), a love-starved, ethically impaired civil servant ("Oslo's,

probably the world's, worst postman," says the first-time director) finds a set of

keys and becomes involved in a bizarre conspiracy. With this darkly funny thriller –

winner of the Critics' Week prize at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival – Sletaune has

been hailed as leading a Norwegian New Wave of filmmaking and has been compared to Aki

Kaurismäki and Jim Jarmusch for his skewed view of urban misfits. One critic has already

called the emotional outcasts who lurch through this dry comedy-drama a cross between the

Czech New Wave and David Lynch, and that's a sentiment hard to improve upon. If

off-the-wall humor is what you seek, Junk Mail – which has been selected for

the Film Society of Lincoln Center's New Directors/New Films program later in the spring

and will be distributed in America by Lion's Gate Films – is a special delivery

indeed.

Valery Todorovsky's delicate, absorbing Russian

drama The Land of the Deaf (Competition) was among the most underrated movies of

the festival, prompting immediate reactions of "too long" and

"unfocused" from the critical corps. Few argued the merits of the lead

performers, however: Chulpan Khamatova and Dina Korzun are both mesmerizing as the waif

who escapes a conniving boyfriend and the deaf stripper who befriends her. True, the

gangster elements of the tale ring less true than the deepening friendship between the two

women, but Alexei Aigi's noteworthy score and Yuri Shaigardanov's evocative location

photography go a long way towards aiding the fragile, otherworldly atmosphere Todorovsky

aims for – and hits. Audiences are required to work for their pleasure in The Land

of the Deaf, but their efforts do not go unrewarded.

This year's prime example of the aging but still

effective term "Europudding," Left Luggage (Competition) marks an assured

directing debut from actor Jeroen Krabbe (The Fugitive) that is at once resolutely

serious and severely undercut by a profoundly miscast leading role. Add to this the

conflicting accents and acting styles of almost every other performer in sight, and the

result is a well-intentioned film that comes across as amateurish in the extreme. The main

culprit is young British actress Laura Fraser, who plays a free-spirited Jewish woman in

1972 Antwerp who reluctantly goes to work as a nanny for the Kalmans, an Orthodox Hassidic

family with five children. As she clashes with Mrs. Kalman (Isabella Rossellini, of all

people, in – of all things – the film's standout performance) and more fiercely

with her husband (Krabbe), Laura also develops a strong bond with their introverted

4-year-old son Simcha (Adam Monty). The closer these two become, and the more successful

Laura is at drawing Simcha out of his self-imposed shell, the more obvious it becomes that

something tragic must happen. Serious subplots involving anti-Semitism, prejudice and

culture clashes are sabotaged at every turn by two-dimensional characterizations (David

Bradley's bigoted building superintendent is the most egregious example), but it is the

wildly overmodulated Fraser who throws the film most out of balance, coming on like a

British cross between Julia Roberts and Alanis Morissette when something must more subtle

is called for. While she may indeed have talent, being asked to carry a film such as this

is a cruel way to break into the business. This year's prime example of the aging but still

effective term "Europudding," Left Luggage (Competition) marks an assured

directing debut from actor Jeroen Krabbe (The Fugitive) that is at once resolutely

serious and severely undercut by a profoundly miscast leading role. Add to this the

conflicting accents and acting styles of almost every other performer in sight, and the

result is a well-intentioned film that comes across as amateurish in the extreme. The main

culprit is young British actress Laura Fraser, who plays a free-spirited Jewish woman in

1972 Antwerp who reluctantly goes to work as a nanny for the Kalmans, an Orthodox Hassidic

family with five children. As she clashes with Mrs. Kalman (Isabella Rossellini, of all

people, in – of all things – the film's standout performance) and more fiercely

with her husband (Krabbe), Laura also develops a strong bond with their introverted

4-year-old son Simcha (Adam Monty). The closer these two become, and the more successful

Laura is at drawing Simcha out of his self-imposed shell, the more obvious it becomes that

something tragic must happen. Serious subplots involving anti-Semitism, prejudice and

culture clashes are sabotaged at every turn by two-dimensional characterizations (David

Bradley's bigoted building superintendent is the most egregious example), but it is the

wildly overmodulated Fraser who throws the film most out of balance, coming on like a

British cross between Julia Roberts and Alanis Morissette when something must more subtle

is called for. While she may indeed have talent, being asked to carry a film such as this

is a cruel way to break into the business.

Set for airing on public television stations in the US later in the

spring, Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart (Panorama) was probably doomed from the start

to be static, given the electric nature of it's subject. From his early days in a New York

band "so bad we had to change our name every week to get work," through the

heyday of The Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol's downtown factory scene and on to his

varied and often cryptic solo career (yes, there's a bit on Metal Machine Music), Reed's

intensity comes through loud and clear in this rigorously chronological survey. Yet for

all it's music-fuelled energy, the movie's gambit of using then-and-now portraiture to

frame it's interviewees blows up in the face of director and turns a kinetic career into a

progression of talking heads. Having said that, the movie is also a priceless addition to

available film and documentation on the subject, who is one of the greatest composers and

difficult performers of the late 20th century. Set for airing on public television stations in the US later in the

spring, Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart (Panorama) was probably doomed from the start

to be static, given the electric nature of it's subject. From his early days in a New York

band "so bad we had to change our name every week to get work," through the

heyday of The Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol's downtown factory scene and on to his

varied and often cryptic solo career (yes, there's a bit on Metal Machine Music), Reed's

intensity comes through loud and clear in this rigorously chronological survey. Yet for

all it's music-fuelled energy, the movie's gambit of using then-and-now portraiture to

frame it's interviewees blows up in the face of director and turns a kinetic career into a

progression of talking heads. Having said that, the movie is also a priceless addition to

available film and documentation on the subject, who is one of the greatest composers and

difficult performers of the late 20th century.

Not since

the advent of Godard and Truffaut has a first feature about disaffected youth drawn such

rave notices as young French director Manuel Prada's Marie baie des anges (European

Film Market). On a French Riviera strangely bereft of adults, sullen 15-year-old petty

thief Orso (Frédéric Malgras) finds his muse in 14-year-old Bardot lookalike Marie

(Vahina Giocante), who entertains American servicemen nearby. Fragmented, hallucinatory

and engrossing, their adventures, far from exploitative, tap with authenticity into the

motiveless amorality that has societies fretting the world over. Pradal has made a savage

yet tender film ("Baie des anges" – Bay of Angels – is a rock

outcropping resembling twin angel shark fins) in which the sad fate of its protagonists

provokes a decisive understanding of the spiritual void that leads to their downfall. Breathless,

indeed. Marie baie des anges will be distributed in the United States by Sony

Pictures Classics, who apparently plan to release the film under it's original title,

perhaps hoping to capitalize on the movie's seductive mystique. Not since

the advent of Godard and Truffaut has a first feature about disaffected youth drawn such

rave notices as young French director Manuel Prada's Marie baie des anges (European

Film Market). On a French Riviera strangely bereft of adults, sullen 15-year-old petty

thief Orso (Frédéric Malgras) finds his muse in 14-year-old Bardot lookalike Marie

(Vahina Giocante), who entertains American servicemen nearby. Fragmented, hallucinatory

and engrossing, their adventures, far from exploitative, tap with authenticity into the

motiveless amorality that has societies fretting the world over. Pradal has made a savage

yet tender film ("Baie des anges" – Bay of Angels – is a rock

outcropping resembling twin angel shark fins) in which the sad fate of its protagonists

provokes a decisive understanding of the spiritual void that leads to their downfall. Breathless,

indeed. Marie baie des anges will be distributed in the United States by Sony

Pictures Classics, who apparently plan to release the film under it's original title,

perhaps hoping to capitalize on the movie's seductive mystique.

Motel Cactus (Forum) is an anomaly in the current South

Korean film scene, both for it's eye-catching visuals (by cinematographer Christopher

Doyle, very much in demand by Asian filmmakers) and the unique sensibilities of assistant

director-producer Park Ki-Yong, who makes a distinctive if somewhat exasperating

directorial debut. Essentially four episodes involving six characters who meet to have sex

in room 407 of the title flophouse (they're apparently called "Love Hotels" in

Seoul), the movie is stylish but often inscrutable, substituting camera movement and

chiarascuro for plot development – the angst-ridden characters are often inarticulate

anyway. "I don't think it's in many way foreign or non-Korean," the director

told an interviewer. "In fact, it contains many moments and images which are very

Korean... and which are exactly what I wanted." He may have gotten what he wanted,

but for the rest of the world Motel Cactus (winner of the New Currents Award at the

1997 Pusan Film Festival) may leave a very different kind of yearning.

French master Alain Resnais has been making movies

that are at once mischievous and magnificent for nearly half a century (a list that

includes Hiroshima Mon Amour, Last Year at Marienbad, Muriel and My

American Uncle), and what is perhaps most extraordinary about this extraordinary

filmmaker is that at the age of 76 anyone would be capable of making a movie as light yet

complicated, as sly yet spry, as the thoroughly enjoyable divertissement Same Old Song

(Competition). Fans of "The Singing Detective" will recognize this premise

immediately, and Resnais short-circuits that potential criticism by dedicating the film to

the late Dennis Potter. The story involves a group of people in and around Paris and their

tangled commitments, a narrative that is punctuated frequently by characters breaking into

straight-faced snippets of classic French pop songs (Jane Birkin even pops up in one scene

and does, you guessed it, a Jane Birkin song). While potential American distributors are

bound to be nervous due to the limited appeal of the music clips, they're just the

frosting on this delicious confection of miscommunication and yearning, as the lyrics of

each song manage to be far more eloquent than the often banal but never boring characters.

Delightfully unique, Same Old Song is a joy from beginning to end. French master Alain Resnais has been making movies

that are at once mischievous and magnificent for nearly half a century (a list that

includes Hiroshima Mon Amour, Last Year at Marienbad, Muriel and My

American Uncle), and what is perhaps most extraordinary about this extraordinary

filmmaker is that at the age of 76 anyone would be capable of making a movie as light yet

complicated, as sly yet spry, as the thoroughly enjoyable divertissement Same Old Song

(Competition). Fans of "The Singing Detective" will recognize this premise

immediately, and Resnais short-circuits that potential criticism by dedicating the film to

the late Dennis Potter. The story involves a group of people in and around Paris and their

tangled commitments, a narrative that is punctuated frequently by characters breaking into

straight-faced snippets of classic French pop songs (Jane Birkin even pops up in one scene

and does, you guessed it, a Jane Birkin song). While potential American distributors are

bound to be nervous due to the limited appeal of the music clips, they're just the

frosting on this delicious confection of miscommunication and yearning, as the lyrics of

each song manage to be far more eloquent than the often banal but never boring characters.

Delightfully unique, Same Old Song is a joy from beginning to end.

Turn a German intellectual loose on the gay porn

scene in Los Angeles and you'll get a film like Sex/Life in L.A. (Panorama), in

which director Jochen Hick (who studied in Hamburg and Bologna through much of the 1980s)

leads the audience on a guided tour of nine men and their freewheeling lifestyles under

the Southern California sun. Subjects include gay movie superstar Matt Bradshaw,

supermodel Tony Ward (he used to date Madonna), photographer Rick Castro, performance

artist/masochist Ron Athey and various other wannabes whose stories are much less, ah,

inspiring. "I wanted to show the real people behind these sex icons," explained

Hick. The movie is interesting for those in to such things, but don't look for this

moderately explicit documentary to show up on public TV any time soon. Turn a German intellectual loose on the gay porn

scene in Los Angeles and you'll get a film like Sex/Life in L.A. (Panorama), in

which director Jochen Hick (who studied in Hamburg and Bologna through much of the 1980s)

leads the audience on a guided tour of nine men and their freewheeling lifestyles under

the Southern California sun. Subjects include gay movie superstar Matt Bradshaw,

supermodel Tony Ward (he used to date Madonna), photographer Rick Castro, performance

artist/masochist Ron Athey and various other wannabes whose stories are much less, ah,

inspiring. "I wanted to show the real people behind these sex icons," explained

Hick. The movie is interesting for those in to such things, but don't look for this

moderately explicit documentary to show up on public TV any time soon.

The raw power of writer-director Carine Adler's Under

the Skin (European Film Market) comes from her bold mixture of overused elements

– grainy photography, unmatched jump-cut editing, slow motion, trendy soundtrack

(think Massive Attack) – in the service of an original story acted with frightening

abandon by spectacular newcomer Samantha Morton, who plays a young woman distraught by the

death of her mother.  As

the 19-year-old Iris sinks into a vortex of self-destructive behavior in an urban

environment consciously devoid of recognizable landmarks, it takes a great force of will

– following a final plunge – to pull Iris from her amoral void. "I set out

to represent a truly female experience on film," said Adler, who made shorts and

documentaries (including the similarly-themed Fever, with Katrin Cartlidge) after

graduating from London's National Film and Television School. "I wanted to write

something multi-faceted, to create a complicated character – an anti-heroine if you

like. So often in films, women are split into good or bad, defined along conventional

lines." Already the winner of prizes at the Toronto and Edinburgh festival, the

decidedly unconventional and noteworthy Under the Skin has screened to great

acclaim at the Venice and Sundance festivals and will be featured later in the spring at

the Film Society of Lincoln Center's New Directors/New Films program. As

the 19-year-old Iris sinks into a vortex of self-destructive behavior in an urban

environment consciously devoid of recognizable landmarks, it takes a great force of will

– following a final plunge – to pull Iris from her amoral void. "I set out

to represent a truly female experience on film," said Adler, who made shorts and

documentaries (including the similarly-themed Fever, with Katrin Cartlidge) after

graduating from London's National Film and Television School. "I wanted to write

something multi-faceted, to create a complicated character – an anti-heroine if you

like. So often in films, women are split into good or bad, defined along conventional

lines." Already the winner of prizes at the Toronto and Edinburgh festival, the

decidedly unconventional and noteworthy Under the Skin has screened to great

acclaim at the Venice and Sundance festivals and will be featured later in the spring at

the Film Society of Lincoln Center's New Directors/New Films program.

In Nicholas Barker's British-American co-production Unmade

Beds (European Film Market), four lonely New Yorkers share their hopes, dreams and

dating service adventures with the camera, punctuated with shots of skylines, or people

observed through apartment windows, or clouds, or personal hygiene products from each

character's bathroom – as well as the unmade beds that each seem to have. Variously

described by critics as "a fly on the wall turned into a vulture" and "the

most sadistic director in British television," Barker studied anthropology before

making his mark on British culture with the satiric BBC series "Washes Whiter,"

"Signs of the Times" and "From A to B." For this unashamedly

manipulative blend of fact and fiction ("an exercise in mendacity," he calls

it), Barker recruited a research staff to pose as singles to find these four, uh,

specimens. Courageous, cruel and monstrously funny, Unmade Beds is among the most

audacious feature film debuts of the year.

Being at the European premiere of an American film –

especially a movie as American as Barry Levinson's David Mamet-scripted Wag the Dog (Competition) – always provides multiple

thrills. First, it's a blast of home after some time in another culture (and Wag the

Dog is nothing if not a wink-wink nudge-nudge blast of America); and second, it

affords the opportunity to see how such a movie "plays" to international

journalists (a word on this: as discerning as they like to see themselves, the global

community of movie critics goes nuts when they're in the same room – or anywhere near

– a recognizable American movie star. The Robert De Niro press conference was as

close to a riot as is possible without actually overturning anything). The movie itself,

winner of a Silver Berlin Bear (Special Jury Prize), seemed to be appreciated at least as

much for it's sheer star power as for the wry message of media manipulation that through a

trick of history parallels current events. Being at the European premiere of an American film –

especially a movie as American as Barry Levinson's David Mamet-scripted Wag the Dog (Competition) – always provides multiple

thrills. First, it's a blast of home after some time in another culture (and Wag the

Dog is nothing if not a wink-wink nudge-nudge blast of America); and second, it

affords the opportunity to see how such a movie "plays" to international

journalists (a word on this: as discerning as they like to see themselves, the global

community of movie critics goes nuts when they're in the same room – or anywhere near

– a recognizable American movie star. The Robert De Niro press conference was as

close to a riot as is possible without actually overturning anything). The movie itself,

winner of a Silver Berlin Bear (Special Jury Prize), seemed to be appreciated at least as

much for it's sheer star power as for the wry message of media manipulation that through a

trick of history parallels current events.

Coincidentally, the alphabetical format of this

report allows the best to be saved until last: Tom Tykwer's sophomore effort (following

the affecting Deadly Maria), Winter Sleepers (New German Films) was easily

the high point of this year's festival, a complex, stunningly photographed wide-screen

drama in which the random acts of a group of only vaguely-related characters conspire with

fate and chance to produce shattering epiphanies for all concerned. In a tiny mountain

village, nurse Laura (Marie-Lou Sellem) shares her childhood home with attractive

translator Rebecca (Floriane Daniel), who often entertains her shallow ski instructor

boyfriend Marco (Heino Ferch). While visiting after a trip, Marco leaves his car door open

and the automobile is borrowed for a drive by slightly tipsy projectionist René (Ulrich

Matthes) – who is promptly involved in a horrible road accident with farmer Theo

(Josef Bierbichler). From there it is only a matter of time before little

misunderstandings lead to huge miscalculations: Rebecca and Marco bicker, Laura begins

dating the strange René, and tragedy is just around the corner. As hypnotic a film as has

been seen in recent memory, Winter Sleepers is for the receptive viewer an

overwhelmingly absorbing and rewarding experience, a disconcerting trip through randomness

that shows Tykwer to be in frighteningly authoritative control of the medium. Currently

without an American distributor, the film will show at a number of upcoming film

festivals, including Filmfest DC in the nation's capital. Coincidentally, the alphabetical format of this

report allows the best to be saved until last: Tom Tykwer's sophomore effort (following

the affecting Deadly Maria), Winter Sleepers (New German Films) was easily

the high point of this year's festival, a complex, stunningly photographed wide-screen

drama in which the random acts of a group of only vaguely-related characters conspire with

fate and chance to produce shattering epiphanies for all concerned. In a tiny mountain

village, nurse Laura (Marie-Lou Sellem) shares her childhood home with attractive

translator Rebecca (Floriane Daniel), who often entertains her shallow ski instructor

boyfriend Marco (Heino Ferch). While visiting after a trip, Marco leaves his car door open

and the automobile is borrowed for a drive by slightly tipsy projectionist René (Ulrich

Matthes) – who is promptly involved in a horrible road accident with farmer Theo

(Josef Bierbichler). From there it is only a matter of time before little

misunderstandings lead to huge miscalculations: Rebecca and Marco bicker, Laura begins

dating the strange René, and tragedy is just around the corner. As hypnotic a film as has

been seen in recent memory, Winter Sleepers is for the receptive viewer an

overwhelmingly absorbing and rewarding experience, a disconcerting trip through randomness

that shows Tykwer to be in frighteningly authoritative control of the medium. Currently

without an American distributor, the film will show at a number of upcoming film

festivals, including Filmfest DC in the nation's capital.

Bonus Round: It is still entirely unclear what

it was doing there – particularly since it only screened once, and then in the

evening – but Jim Jarmusch's The Year of the Horse

(European Film Market) proved to be just the sonic break so desperately needed by the

motley group that wandered in after a particularly heavy movie to kill some time before a

festive meal. And when it was discovered that a member of the exhausted posse was seated

directly adjacent to the volume control on the back wall of the tiny theater, sonic

nirvana soon followed. There's nothing like a blast of home to refresh a weary traveller,

and beyond it's inestimable value as a document of some three decades in the musical life

of Neil Young and Crazy Horse, the movie served as a much-needed battery recharger in the

late innings of a festival that needs to be experienced to be completely appreciated. Bonus Round: It is still entirely unclear what

it was doing there – particularly since it only screened once, and then in the

evening – but Jim Jarmusch's The Year of the Horse

(European Film Market) proved to be just the sonic break so desperately needed by the

motley group that wandered in after a particularly heavy movie to kill some time before a

festive meal. And when it was discovered that a member of the exhausted posse was seated

directly adjacent to the volume control on the back wall of the tiny theater, sonic

nirvana soon followed. There's nothing like a blast of home to refresh a weary traveller,

and beyond it's inestimable value as a document of some three decades in the musical life

of Neil Young and Crazy Horse, the movie served as a much-needed battery recharger in the

late innings of a festival that needs to be experienced to be completely appreciated.

| |

|