|

| |

U-Turn

Review by Carrie

Gorringe

Posted 3 October 1997

|

|

Directed by Oliver Stone Starring Sean Penn, Jennifer Lopez,

Nick Nolte, Powers Boothe,

Claire Danes, Joaquin Phoenix,

and Billy Bob Thornton.

Screenplay by John Ridley,

from his novel, Stray Dogs |

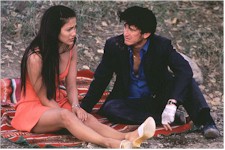

Con man Bobby Cooper (Penn) is

heading for Las Vegas in the hopes of clearing a rather large gambling debt owed to a

rather vicious individual whose idea of giving people a break on their loans has to do

with the liberal application of a sledgehammer to the deadbeat’s shins. His good luck

evaporates just outside of a hellhole ironically named Superior, Arizona, when a rad hose

decides to give out. This bad break puts him at the mercy of several local grotesqueries,

least of which is the local "mechanic," Darrell (Thornton), who continually

raises the ante on getting Cooper’s car released from automotive custody.  Next in line are the

McKennas. Lured by the beauty of sultry Grace (Lopez), Cooper soon finds himself

confronted by her beast of a husband, Jake (Nolte), the closest thing this geographic

exercise in hell has to a powerhouse. Cooper discovers that both participants in the

McKenna marriage would be more than happy to eliminate the high financial cost of divorce

by eliminating each other, and Cooper becomes the device of choice for both. While he

ponders which offer to take, he is periodically assaulted by the vacuousness flirting of

the local dimwitted floozy (Danes) and her hysterically jealous boyfriend (Phoenix). The

local sheriff (Boothe) also has this newcomer under surveillance. Cooper might have left

this madhouse much sooner, if his money hadn’t been, well, liquidated in a robbery at

Superior’s only general store. Now, even the loanshark is after him. Desperate,

exhausted, broke and under Grace’s spell, the weak-willed Cooper has to make a

decision: to help Grace or to help Jake? Next in line are the

McKennas. Lured by the beauty of sultry Grace (Lopez), Cooper soon finds himself

confronted by her beast of a husband, Jake (Nolte), the closest thing this geographic

exercise in hell has to a powerhouse. Cooper discovers that both participants in the

McKenna marriage would be more than happy to eliminate the high financial cost of divorce

by eliminating each other, and Cooper becomes the device of choice for both. While he

ponders which offer to take, he is periodically assaulted by the vacuousness flirting of

the local dimwitted floozy (Danes) and her hysterically jealous boyfriend (Phoenix). The

local sheriff (Boothe) also has this newcomer under surveillance. Cooper might have left

this madhouse much sooner, if his money hadn’t been, well, liquidated in a robbery at

Superior’s only general store. Now, even the loanshark is after him. Desperate,

exhausted, broke and under Grace’s spell, the weak-willed Cooper has to make a

decision: to help Grace or to help Jake?

Many comparisons have been made between U-Turn and its presumed

predecessors in film noir; one critic referred to the film as Touch of

Evil mixed with Duel in the Sun. Stone himself prefers to think of U-Turn

as more of a western than a noir piece. A more immediate comparison might be made

between U-Turn and John Dahl's 1993 neo-noir, Red Rock West.

However, in terms of narrative structure, U-Turn’s closest cinematic

"relative" really has to be the Edgar G. Ulmer noir classic from 1946, Detour.

Both films share the common dilemma of a spineless antihero caught in a relentlessly

downward spiral, a position exacerbated by allowing a sinister female into his life.  Every more he takes to

extricate himself just causes the level of misery to accelerate. Not surprisingly, this

type of noir can be extremely difficult for the audience to tolerate for very long,

precisely because the grim route taken by the antihero is so lacking in self-awareness

that, under the force of an overwhelmingly negative pressure-cooker atmosphere, disgust

mixed with despair soon sets in – a fatal combination of forces with which to hold an

audience in thrall. However, because of studio and budgetary considerations (the film was

shot over four days), Ulmer was obliged to keep the torture down to sixty-nine minutes of

running time; these factors saved Detour from becoming a B-movie exercise in

nihilistic self-indulgence and rendered it a minor masterpiece in retrospect. Just as Detour

began to tax the nerves beyond endurance, the ending, with its macabre twist, intervened

to save everyone from nervous enervation. In this case, it was better to end the downbeat

on the upbeat. Every more he takes to

extricate himself just causes the level of misery to accelerate. Not surprisingly, this

type of noir can be extremely difficult for the audience to tolerate for very long,

precisely because the grim route taken by the antihero is so lacking in self-awareness

that, under the force of an overwhelmingly negative pressure-cooker atmosphere, disgust

mixed with despair soon sets in – a fatal combination of forces with which to hold an

audience in thrall. However, because of studio and budgetary considerations (the film was

shot over four days), Ulmer was obliged to keep the torture down to sixty-nine minutes of

running time; these factors saved Detour from becoming a B-movie exercise in

nihilistic self-indulgence and rendered it a minor masterpiece in retrospect. Just as Detour

began to tax the nerves beyond endurance, the ending, with its macabre twist, intervened

to save everyone from nervous enervation. In this case, it was better to end the downbeat

on the upbeat.

Unfortunately, this is not the tack taken by Stone and Ridley. The

problem doesn’t stem from the traditional sources of too much money and too much time

for shooting (Stone, to his credit, shot U-Turn for twenty million dollars – a

veritable fire-sale price in contemporary Hollywood – and in forty-two days, almost a

third less time than is normal for him).  Had the two also employed economy in crafting the plot structure,

everything should have worked out according to plan. Instead, they allow events in

Superior, Arizona to drag out endlessly for at least half an hour too long. There

aren’t enough unique plot variations suggested by the environment to effectively

nurture this delay (cities are a better setting for this type of film, suggesting, as they

do, a myriad of possibilities denied to your average one-horse hamlet), so Stone and

Ridley are reduced to piling devastation upon devastation on Cooper’s back as a form

of filler, and the efforts seem so contrived that they simply seem ludicrous. By the time

the film gets itself back on the road, to what otherwise would have been (should have

been?) a stunning finale, the film’s momentum has been inexorably depleted, as the

audience’s interest has been strung past the breaking point. Forget the concept of

"compassion fatigue;" the audience with which I saw U-Turn was suffering

from something far more severe: "identification fatigue;" the audience had

nothing left to give to the film, and simply wanted the conclusion to emerge as quickly as

possible. Not even generous amounts of over-the-top humor and immaculate, striking visuals

could salvage it. Had the two also employed economy in crafting the plot structure,

everything should have worked out according to plan. Instead, they allow events in

Superior, Arizona to drag out endlessly for at least half an hour too long. There

aren’t enough unique plot variations suggested by the environment to effectively

nurture this delay (cities are a better setting for this type of film, suggesting, as they

do, a myriad of possibilities denied to your average one-horse hamlet), so Stone and

Ridley are reduced to piling devastation upon devastation on Cooper’s back as a form

of filler, and the efforts seem so contrived that they simply seem ludicrous. By the time

the film gets itself back on the road, to what otherwise would have been (should have

been?) a stunning finale, the film’s momentum has been inexorably depleted, as the

audience’s interest has been strung past the breaking point. Forget the concept of

"compassion fatigue;" the audience with which I saw U-Turn was suffering

from something far more severe: "identification fatigue;" the audience had

nothing left to give to the film, and simply wanted the conclusion to emerge as quickly as

possible. Not even generous amounts of over-the-top humor and immaculate, striking visuals

could salvage it.

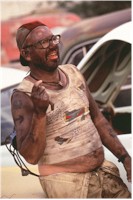

The larceny committed upon U-Turn by its own makers, which can

only be described as vampiric, is inexcusable because there are a number of grand

performances in this ensemble cast. Obviously, Penn, with his multilayered portrayal of

the freedom-craving Cooper confirms his position as one of the finest actors of his

generation, but Phoenix, remembered best as the teenage killer in To Die For,

carves out a new dimension for himself as TNT, the teenage nut case. Nolte is extremely

impressive as the evil Jake, and Thornton is underhandedly brilliant as the malevolently

hilarious mechanic. Unfortunately, U-Turn takes all of their talents into a dead

end.

Contents | Features

| Reviews | Books | Archives | Store

Copyright © 1999 by Nitrate Productions, Inc. All Rights

Reserved.

| |

|