|

| |

Hoodlum

Review by Carrie

Gorringe

Posted 29 August 1997

|

|

Directed by Bill Duke Starring Laurence Fishburne,

Vanessa Williams,Tim Roth, Andy Garcia,

Cicely Tyson, Chi McBride,

William Atherton, and Loretta Devine

Screenplay by Chris Brancato |

At its very heart, Hoodlum

is a film about dishonesty, a dishonesty not restricted to the desire of Dutch Schultz

(Roth) and Charles "Lucky" Luciano (Garcia) to control the numbers racket in

Harlem during the 1930s by any means available. No, the real speciousness comes from the

film’s desire to rewrite history in the most shameless fashion to suit God knows what

purpose, although the two main contenders are political correctness and/or a need to

distort facts to keep the plot from falling into redundancy.

Briefly put, history records that the Italian Mafia, after a brief and bloody power

struggle during the early 1930s, was fashioned into an efficient unit (comprising five

families which divided up all of the territory in New York (check)) that answered to

Luciano.  This unit

then embarked on what might politely be deemed a takeover of the vices still controlled by

the remaining Irish, Jewish and African-American gangs. With ethnic cohesiveness, lots of

cash from Prohibition bootlegging, and few scruples about using violence on their side,

the Italian gangsters achieved their aims by the mid-‘30s – just in time for

Luciano to head for a stretch in Dannemora prison on a trumped-up prostitution charge and

eventual deportation from the United States. Luciano’s travel plans were the result

of the efforts of one ambitious and mob-loathing D.A. ,Thomas Dewey. Even Luciano’s

influence over the dockworkers’ unions during World War II to prevent the

infiltration of foreign spies (he also arranged for the Sicilian Mafia to facilitate the

1944 Allied landings in Sicily) wasn’t enough to buy him succor from Dewey. Dewey,

now Governor of new York State and well on his way to securing the 1948 Republican

presidential nomination, wasn’t about to jeopardize his political future to keep a

promise to someone who wasn’t good at keeping promises himself . In the battle of

ambition versus ambition, Luciano lost heavily; he spent the rest of his life in Italy,

always homesick for America. Only in death – when he couldn’t do any more harm

– was Luciano allowed to return, but, like Caesar, whatever good he did was buried

with him. This unit

then embarked on what might politely be deemed a takeover of the vices still controlled by

the remaining Irish, Jewish and African-American gangs. With ethnic cohesiveness, lots of

cash from Prohibition bootlegging, and few scruples about using violence on their side,

the Italian gangsters achieved their aims by the mid-‘30s – just in time for

Luciano to head for a stretch in Dannemora prison on a trumped-up prostitution charge and

eventual deportation from the United States. Luciano’s travel plans were the result

of the efforts of one ambitious and mob-loathing D.A. ,Thomas Dewey. Even Luciano’s

influence over the dockworkers’ unions during World War II to prevent the

infiltration of foreign spies (he also arranged for the Sicilian Mafia to facilitate the

1944 Allied landings in Sicily) wasn’t enough to buy him succor from Dewey. Dewey,

now Governor of new York State and well on his way to securing the 1948 Republican

presidential nomination, wasn’t about to jeopardize his political future to keep a

promise to someone who wasn’t good at keeping promises himself . In the battle of

ambition versus ambition, Luciano lost heavily; he spent the rest of his life in Italy,

always homesick for America. Only in death – when he couldn’t do any more harm

– was Luciano allowed to return, but, like Caesar, whatever good he did was buried

with him.

Hoodlum,

however, would have us believe that Dewey (Atherton) was a corrupt official who

wasn’t reluctant to accept a well-equipped suitcase of payoff money, and that Dutch

Schultz’s reign of terror over Harlem lasted until 1937, when the victorious Harlem

factions won out (in fact, Schultz was murdered in 1935 on Luciano’s orders because

Schultz wanted to assassinate Dewey, a move which other mobsters feared would be fatal to

their health). The last thing that Luciano feared was the movement uptown of ballsy Harlem

numbers runners like Stephanie St. Clair (Tyson) or her associate, "Bumpy"

Johnson (Fishburne); white government officials scared him (if anyone could scare him) far

more. Even if an individual like Bumpy had managed to carve out a niche for himself

against Luciano, the deal would have cost him heavily in terms of monthly tribute.

Admittedly, the film does initially emphasize the risk that Johnson and his compatriots

are taking, but the optimistic conclusion it provides is shamefully dishonest. Hoodlum,

however, would have us believe that Dewey (Atherton) was a corrupt official who

wasn’t reluctant to accept a well-equipped suitcase of payoff money, and that Dutch

Schultz’s reign of terror over Harlem lasted until 1937, when the victorious Harlem

factions won out (in fact, Schultz was murdered in 1935 on Luciano’s orders because

Schultz wanted to assassinate Dewey, a move which other mobsters feared would be fatal to

their health). The last thing that Luciano feared was the movement uptown of ballsy Harlem

numbers runners like Stephanie St. Clair (Tyson) or her associate, "Bumpy"

Johnson (Fishburne); white government officials scared him (if anyone could scare him) far

more. Even if an individual like Bumpy had managed to carve out a niche for himself

against Luciano, the deal would have cost him heavily in terms of monthly tribute.

Admittedly, the film does initially emphasize the risk that Johnson and his compatriots

are taking, but the optimistic conclusion it provides is shamefully dishonest.

All of these polarized and distorted historical elements result in clearly-defined

characterizations, but also burdens the film with a reliance upon insidious reverse

stereotyping. Thus, the audience is treated to the spectacle of noble African-Americans

fighting irremediably scummy Italians and Jews. How can you find fault with a group of

individuals who see preying upon their own as a form of social welfare especially when

Bumpy’s assistant, Illinois Gordon (McBride), sanctimoniously assures the audience

that one good payoff on a numbers game could buy a month’s worth of groceries in

Depression money? It’s very simple: look at the wealth accrued by Mme St. Clair, who,

before being framed, lives in opulent Art Nouveau splendor (there were a few Tiffany lamps

scattered around her main living room), while the people who desperately play the numbers

live in squalor. His protestations to the contrary, Bumpy Johnson’s exclusive

interest lies with Bumpy Johnson. One unfortunate conclusion becomes apparent to anyone

with eyes to see: no matter the color of the numbers runners, the only victims in Harlem

are the poor blacks, who end up in the red every day of their miserable lives.

Hoodlum

reluctantly acknowledges the rampant poverty in 1934 Harlem, and the corruption of the

numbers racket therein, but quickly sweeps these rather uncomfortable facts under the

Aubusson rug, while allowing our eyes to feast on the attraction between Fishburne and

Williams (only the latter half of this pairing is compelling) and the tattered remnants of

a potentially exciting robbers-and-robbers tale, too burdened with its own mendacity to

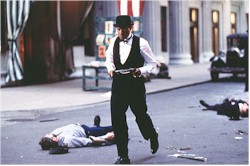

become anything other than a tepid melodrama. Even the more violent scenes, shot in the

quick, disjointed editing style so common these days as to become its own cliché,

inspires only boredom and the hope that they will be dispatched with the same swiftness of

the thugs involved (unfortunately, the audience isn’t that fortunate). Attempting to

dress up this decomposing cinematic corpse in the artificialities of designer history

leaves Hoodlum also very much in the red – in terms of a lack credibility, its

waste of talent, and the monotony that the filmmakers substitute for real dramatic

tension. Director Bill Duke, who also made the uneven, but much more entertaining, A

Rage in Harlem, should have known better than to try his hand at this attempt to

tiptoe through American history with all the subtlety of someone wearing hobnail boots.

Audiences, however, will probably get wise to Hoodlum’s multiple-level

betrayal and take its box-office receipts for a ride. Hoodlum

reluctantly acknowledges the rampant poverty in 1934 Harlem, and the corruption of the

numbers racket therein, but quickly sweeps these rather uncomfortable facts under the

Aubusson rug, while allowing our eyes to feast on the attraction between Fishburne and

Williams (only the latter half of this pairing is compelling) and the tattered remnants of

a potentially exciting robbers-and-robbers tale, too burdened with its own mendacity to

become anything other than a tepid melodrama. Even the more violent scenes, shot in the

quick, disjointed editing style so common these days as to become its own cliché,

inspires only boredom and the hope that they will be dispatched with the same swiftness of

the thugs involved (unfortunately, the audience isn’t that fortunate). Attempting to

dress up this decomposing cinematic corpse in the artificialities of designer history

leaves Hoodlum also very much in the red – in terms of a lack credibility, its

waste of talent, and the monotony that the filmmakers substitute for real dramatic

tension. Director Bill Duke, who also made the uneven, but much more entertaining, A

Rage in Harlem, should have known better than to try his hand at this attempt to

tiptoe through American history with all the subtlety of someone wearing hobnail boots.

Audiences, however, will probably get wise to Hoodlum’s multiple-level

betrayal and take its box-office receipts for a ride.

Contents | Features

| Reviews | News | Archives | Store

Copyright © 1999 by Nitrate Productions, Inc. All Rights

Reserved.

| |

|